What is loss aversion and how to avoid it?

Loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains: loss aversion implies that someone who loses $100 will be more disappointed than another person will be happy from receiving a $100 windfall1. Some studies have even suggested that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. This principle of loss aversion is very prominent in investing and in constructing portfolios designed to achieve investor’s long-term objectives.

As investors, we know that over very long periods stocks have outperformed bonds – by a lot. According to data from Ibbotson SBBI, a dollar invested in U.S. large-cap stocks in 1926 would have grown to $7,353 by the end of 2017. If you invested that same dollar in Treasury bills, it would have become $21. Even when knowing this, we still experience loss aversion when we see the values of our property and investments decrease.

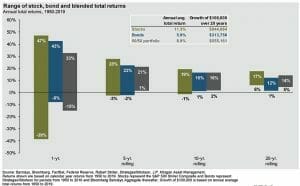

Loss aversion can lead investors to check investment portfolios more frequently. Investors who checked on their portfolios weekly or even daily tend to make decisions as though they had a similar time horizon even though their actual time horizon may be in the decades. Investors’ perception of risk begins to increase as they check on their portfolios more frequently. In reality, investors would be better served to think about their investments in terms of their holding periods. The odds of losing money in risk assets with positive expected returns, like stocks, declines with time. Thus, the longer an investor intends to hold the asset, the more attractive the risk asset will appear, as long as the investment is not evaluated frequently. As seen in the chart below, the longer the holding period, the less risk there is in holding risk assets.

Investors with even as short of a time frame as five years have not experienced a cumulative loss in a blended portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds in any rolling 5-year period in the past 79 years.

The further we remove ourselves from the inexplicable day-to-day gyrations of the market, the less risky we will perceive our investments to be. As a result, the less often we look at our portfolios, the less likely we will be upset and tempted to tinker. Tinkering rarely, if ever, helps us meet our long-term goals. It more likely results in increased costs, both explicit and implicit. The explicit costs include trading costs and taxes. The largest implicit cost of tinkering is opportunity costs. Missing out on tremendous market returns because you have been parked in cash for the past 10 years, still shell-shocked from the last bear market, is an opportunity cost.

Over the long-term, the market should do most of the heavy lifting for us, assuming we just stay along for the ride.

1Loss aversion was first identified by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.

Brad Lyons, CFP®

Posted 4/8/2020

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Wiser Wealth Management, Inc (“Wiser Wealth”) is a registered investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). As a registered investment adviser, Wiser Wealth and its employees are subject to various rules, filings, and requirements. You can visit the SEC’s website here to obtain further information on our firm or investment adviser’s registration.

Wiser Wealth’s website provides general information regarding our business along with access to additional investment related information, various financial calculators, and external / third party links. Material presented on this website is believed to be from reliable sources and is meant for informational purposes only. Wiser Wealth does not endorse or accept responsibility for the content of any third-party website and is not affiliated with any third-party website or social media page. Wiser Wealth does not expressly or implicitly adopt or endorse any of the expressions, opinions or content posted by third party websites or on social media pages. While Wiser Wealth uses reasonable efforts to obtain information from sources it believes to be reliable, we make no representation that the information or opinions contained in our publications are accurate, reliable, or complete.

To the extent that you utilize any financial calculators or links in our website, you acknowledge and understand that the information provided to you should not be construed as personal investment advice from Wiser Wealth or any of its investment professionals. Advice provided by Wiser Wealth is given only within the context of our contractual agreement with the client. Wiser Wealth does not offer legal, accounting or tax advice. Consult your own attorney, accountant, and other professionals for these services.